Economic Activism

About 2 weeks ago I was approached to consider joining the Board of World Rugby which I am exploring but that’s not what I have been asked to share this morning. I have been asked to discuss Economic Activism.

How many people have come across the term Economic Activism? A few years ago I was looking for a title that better describes and reflects what I do, my work and my passion over the last 25 years. I decided, given that there are political activists, environmental activists, social activists etc, that I needed to pioneer the idea of an economic activist and therefore I declared myself one, and I use the title on my business cards. Pretty cool don’t you think? Well I think so!

What is my definition of Economic Activism?

Economic Activism involves using economic power for change, it focuses on the idea of using one’s wealth to represent one’s values and seeks to transform an exploitative economic structure. Economic activism is needed now more than ever given the current state of the economy, and the economic inequality that exists in the world. (What do I mean by wealth?) I am referring to financial resources of course but more importantly, I am referring to what most of us have – that is Knowledge, Experience, Wisdom, Time and Skills that we can use to enable others to improve their lives, change their circumstances, their prospects and progress in life.

I would like to advocate for two models.

Firstly, Economic activism through financial resources can be a contribution towards education, charities addressing various causes, socially responsible investing, or a collaborative sharing of resources. For example, participation of women through Wiphold more than 20 years ago.

Socially responsible investments involve investing to drive changes in the marketplace. For example, Wendy Appelbaum took on the Micro lending industry for exploiting poor people and charging them obscene interest rates. This kind of investing should not just be limited to the wealthy in society, it can be done by any concerned citizen who considers themselves a champion for economic justice. We have a responsibility to influence relevant social issues in society e.g, the crisis in education. For example, in 2015 I became a business partner in an initiative pioneered by Partners for Possibility to share my leadership experience with a school in Daveyton.

Secondly, Economic Activism through mentorship of younger generations, giving away clothes through charity in order to help new graduates who cannot afford work-clothes, giving away toys that our children have outgrown, or serving leftover food to the hungry / less fortunate.

The principle behind economic activism is that of sharing, collaboration, giving, empowerment and helping each other to create the kind of communities we want to live in, where everyone thrives and enjoys a decent quality of living.

Ultimately, we need to use our influence to build responsible economies, to reinforce good behaviour and remove economic exploitation from society. This can only be achieved if you and I become Champions of positive change wherever we witness an injustice. Too many businesses are built by exploiting ignorant, uneducated and unsuspecting consumers. When I grew up it was higher purchase, in the last 30 years it has been Micro lending for example.

To conclude, allow me to borrow from Charlene Fadirepo who proposes 4 strategies for everyday economic activism.

Overall

Economic activism begins with you and I taking responsibility about how we spend our most important resources – time, money and knowledge / vision / experience. It does not matter if we have a little or a lot, those three resources are the tools we have to shape our lives.

Charlene’s 4 Strategies are the following:

1. Live within our means – this is something my mother taught me at a young age. Financial management and financial intelligence are critical tools in life.

2. Support businesses that are responsible – In Africa we consume things that we do not make and we make things we do not consume. We need to change this equation. We must support businesses which reflect our values and principles. Businesses that do not respect our patronage do not deserve our time or money. (Let me unpack what I mean). $1 circulates in Asian Communities for a month, in Jewish Communities about 20 days, in White Communities about 17 days and guess how long in Black Communities? 6 hours.

3. Invest to career advancement and personal development. We all have gifts but they need to be developed.

4. Build wealth for our family.

We should take responsibility to learn about managing money effectively, controlling debt, save from our earnings and acquire assets that grow over time.

In closing, let me remind you that South Africa’s Apartheid system was brought to its knees by economic boycotts of the 70’s and 80’s. Economic activism therefore is a powerful tool for change.

I would welcome your thoughts and reflections. Thank you ladies and gentleman for lending me your ears.

Wendy Luhabe

March 2016

How Economic Activism Can Empower the African Woman

Knowledge@Wharton: You describe yourself as an economic activist. You’re based in South Africa. What is an economic activist?

Wendy Luhabe: In my case, it’s focusing on the participation of women in the economy. When I thought about what we’ve been doing, I realized that you hear of social activists or political activists, but you don’t hear of economic activists. The work we’ve done deserves the description. We pioneered two ventures: the first one was an investment company we started 20 years ago. It mobilized 18,000 women to become investors for the first time through a platform called Women Investment Portfolio Holdings. The company is still in existence. It has a value of about $200 million.

After that, about 10 years later, we started a private equity fund for women, which was also an unheard of concept in the world. There are less than 10 funds that are focusing on women-owned enterprises. This was definitely the first and probably still the only one in Africa.

Knowledge@Wharton: That company still exists as well?

Luhabe: The fund has closed but several of the investments are still in existence.

Knowledge@Wharton: In the private equity company, were you solely focused on investing in women-owned businesses?

Luhabe: Yes.

Knowledge@Wharton: In the first case, it was women investors?

Luhabe: Yes. In the second case, it was investing in companies owned by women. My view is that if we grow the number of women entrepreneurs and give them access to capital and the business expertise to enlarge their businesses, they will contribute towards creating jobs, which is a major challenge in South Africa.

“We wanted to take women beyond that to say, you can provide labor and you can consume, but you can also be an investor responsible for your own financial independence.”

Knowledge@Wharton: How did you come to this? What was your pathway that led to these very bold and entrepreneurial moves?

Luhabe: It was a combination of things. South Africa was becoming a democracy and we had politicians who were committed to gender empowerment and passed legislation that made it possible. So it was largely the environment. Observing that as the political landscape was being rearranged and women were being left out, we decided that we would create our own opportunities rather than wait to be invited. That’s how it happened.

Knowledge@Wharton: You had a background in finance?

Luhabe: I studied commerce. I didn’t work in commerce or finance, but I studied it. I worked in marketing. My first 10 years were in marketing. But the three cofounders came from finance; all three were in banking. That’s why I handpicked them, so that we wouldn’t be ignored because we didn’t understand the industry we were getting into.

Knowledge@Wharton: As an economic activist now, what is the focus of your activities?

Luhabe: Communicate economic empowerment. I’ve invested in a micro bakery project that will have a footprint of about 400 bakeries throughout South Africa. It will enable women to generate an income of 5,000 rand a month — about $500 a month — from zero to $500 a month, making their own bread and supplying it to their immediate neighborhood.

Knowledge@Wharton: You are an investor in this? You helped to grow the business?

Luhabe: I am. I’m identifying economic opportunities that can help uplift communities. The first project we’ve done is the bakery. It’s not mine; it’s an existing project that I have invested in to help scale it. I’ve invested in an agricultural project in the southern part of the country in a community that owns land, but didn’t have the resources to invest in seeds. I discovered that seeds for agriculture are the most expensive part. So I invested to enable them to buy the seeds.

Knowledge@Wharton: In your years of doing this kind of work are there lessons that you’ve learned or that you’ve discovered that are very helpful for scaling these kinds of businesses, for knowing that this bakery is a good idea, it will work and we can scale it?

Luhabe: I can’t answer that because I’m not operational. I’m an investor. So you would need to talk to people who are operational. I’m sure there must be many lessons. Because when you are pioneering and you are on the ground, you’re responding to issues as they develop. I think the tragedy is that those lessons don’t get documented.

Knowledge@Wharton: There’s certainly a lot of interest. To this day you are quite pioneering in bringing women into investing.

Luhabe: It hasn’t been done. When we started it, it had never been done and it still hasn’t been done. I’m not sure why because we’ve traveled extensively to share the idea. Somehow people just haven’t been able to get it off the ground. I don’t know whether in our case it was because of the confluence of a change in the political system and people feeling quite optimistic about the future and the opportunities opening up.

Knowledge@Wharton: If you were to tell us the typical woman who invested in that fund, who was she?

Luhabe: What’s actually quite unique about this is that it mobilized South African women from all walks of life. So there were white women, black women, ordinary women, wealthy women, educated women, uneducated women, rural women, urban women. What we did and how we were able to do that is because we invested two years before the company was established doing a roadshow which was called Beyond Labor and Consumption. We felt that all that women were considered good for in the economy was to provide labor, or we consume, we buy. We wanted to take women beyond that to say, you can provide labor and you can consume, but you can also be an investor responsible for your own financial independence.

It was because of that roadshow. It took us about two years. We have nine provinces in South Africa and it went to every single province and spoke to women from all walks of life.

Knowledge@Wharton: I would imagine that there would be a barrier with married women feeling like they couldn’t invest their family’s wealth, that the men controlled it or the men had to approve. Did you have to win over the men as well?

Luhabe: We actually had men who bought shares for their wives and their daughters and their helpers. South Africa is fortunate. We are lucky that we have help in our homes. So we had a lot of white families who actually bought shares for their helpers as well. So we really mobilized the nation and people got behind it.

Knowledge@Wharton: What are the sort of challenges and opportunities that you’re seeing now for women entrepreneurs in South Africa?

Luhabe: I think it’s the same issues as everywhere else: access to capital, to expertise, the knowhow, the ecosystem. South Africa doesn’t have an ecosystem for entrepreneurs. Although we have a well-established financial services sector, it doesn’t support entrepreneurs. It’s totally risk averse.

“It mobilized South African women from all walks of life. So there were white women, black women, ordinary women, wealthy women, educated women, uneducated women, rural women, urban women.”

We don’t have a venture capital culture. There is an element of angel investing, but it’s still very limited. We have private equity, but private equity doesn’t invest in start-ups. So we have pockets of things. We have lots of government funding, but it doesn’t really reach the opportunities that are in the marketplace because we lack the ecosystem. They just don’t know how to assess projects and opportunities and risks. The funds usually go unspent. They don’t go where they are supposed to go to because of that lack of an ecosystem in the economy.

Knowledge@Wharton: But somehow you broke through this many years ago.

Luhabe: It was because we were right at the beginning, before there were rules and laws and things. We kind of made it up. Sometimes that’s an advantage when there’s nothing in existence, you can make it up.

The empowerment initiatives that existed at the beginning of our democracy were driven by a few individuals who were primarily men. What we started was the first one that mobilized large numbers of individuals, with a focus on women obviously in our case. That was an example of what I think the government intended with economic empowerment, to make it broad based in a meaningful way.

Knowledge@Wharton: Are there any key skillsets or talents or abilities that you feel you had to employ to be successful in this?

Luhabe: Well, three of my cofounders came from the banking sector, so they understood what we were trying to do. We were offering a solution in a sector that we understood. They were known in the industry and they understood the industry.

What I didn’t tell you is that we did two capital raisings from the women themselves. The first was 25 million rand. We needed to do a second one and raised 75 million rand. The first 100 million rand to get this company off the ground and to acquire equity in the various industries came from women themselves. Because of that, by the time we raised institutional funding we had already proven the concept.

Knowledge@Wharton: Where do you see your work taking you over the next five years?

Luhabe: I’m beginning to invest in Africa. I’m going to invest in the food business in Kenya. I’m going to invest in Nigeria. I’m going to begin investing outside South Africa.

Click HERE for more.

The Entrepreneurs Spurring Africa’s Rise

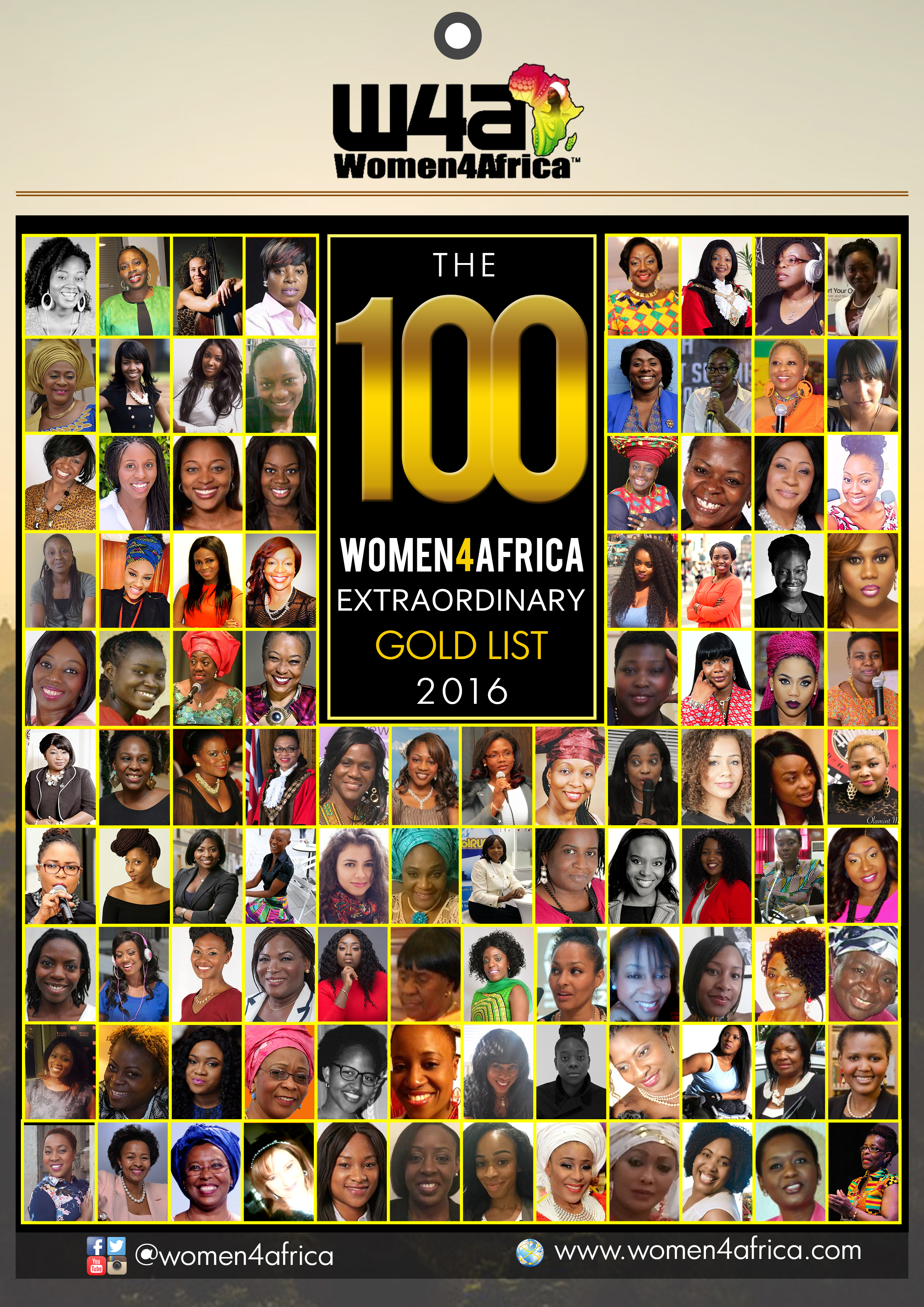

The 100 Women4Africa 2016 ‘Extraordinary Gold List’

In honour of ‘International Women’s Day’ Women4Africa have released its ‘100 Women4Africa Extraordinary Gold List 2016’ which comprises of all of its 2016 Recognitions and Finalists. Click HERE

Every year Women4Africa celebrates a plethora of outstanding women and youth so this year see’s the Launch of its ‘Extraordinary Gold List’ which will be a yearly feature.

The REAL gold of Africa is its ‘Women’ and what better way to celebrate them.

The list as follows

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN WOMAN RECOGNITION

HRH Lady Julia Osei Tutu

Arunma Oteh

Dr Snowy Khoza

Wendy Luhabe

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY RECOGNITION

Clara Agyeman

Mercy Mugure

Peggy Mkhoto

UK RECOGNITION

Oluyemisi Aiyegbusi

Cecilia Anim

Anne Wafula Strike

Sherry Ann Dixon

Jenny Okafor

Funke Abimbola

FINALISTS

Oye Oyimale

Nadine Peters

Yvonne Yvette

Toyin Seweje

Akosua Afriyie-Kumi

Jacqueline Onalo

Ava Brown

Kemi Tomide Johnson

Sheila Elliott

Tokie Laotan Brown

Sheila Ruiz

Seyi Olusanya

Janet Wanaina

Sandra Nelson

Vanessa Oluwole

Jessica Laditan

Phoebe Ruguru

Maria Leo Johnson

Audrey Babibanga

Mabel Ogundayo

Bisola Babalola

Claudine Adeyemi

Evelyn Asante

Kanayo Dike Oduah

Munah E. Pelham-Youngblood

Mercy Kudakwashe

Damilola Balogun

Phinnah Ikeji

Sonia Meggie

Melissa Emmanuel

Seyi Oluwamayowa

Victoria Lawrence

Olamidotun Akinrosotu

Victoria Idowu

Mary Akangbe

Marsha Jones

Imambay Kamara

Gloria Awosika

Chika Russell

Foluke Akinlose

Denise Nurse

Bamidele Seun Owoola

Folayemi Olaitan

Nathalie Richards

Peace Hyde

Rashida Abdulai

Rhoda Wilson

Bilikisu Labaran

Miranda Brawn

Liz Onabowu

Aya Chebbi

Chi-chi Nwanoku

Placida Acheru

Morenike Ajayi

Wambui Njau

Ronke Udofia

Lindani Moyo

Cllr Susan Fajana Thomas

Marsha Powell

Ayo Sonoiki

Claire Clottey

Abe Jawando Tade

Ini Usanga

Cynthia Masiyiwa Mukoko

Norma Gregory

Sade Etti

Nisha Maharaj

Dr Bc Esuruso

Lalita Junggee

Tola Akerele

Toyin Lawani

Mimi Kalinda

Yemi Adenuga

Nancy Kacungira

Doris Kwaka

Adeola Fayehun

Mofoluwaso Ilevbare

Robel Neajai Pailey

Oulimata Sarr

Dr Joyce Akumaa Dongotey-Padi

Adebola Salako

Marguerite Barankitse

Vivian Onano

Keturah Shammah

Itoro Eze Anaba

Nikki Laoye

And to round it off at 100 we included Women4Africa Founder.

To see all our 2016 Recognitions & Finalists see http://women4africa.com/2016-recognitions-finalists/

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- …

- 15

- Next Page »